To realize the potential of public-private talent exchanges, however, it is also necessary to account for their challenges. Below is a discussion of potential exchange hurdles—which are related to policy design; program implementation and administration; ethical and legal issues; exchange recruitment and selection; goals, roles and position alignment; and post-exchange issues.

Policy Design

To be effective and ethical, talent exchange programs need to be built on clear policy guidelines informed by agency needs, goals and capacity. Ambiguities or oversights in the enabling legislation—even if inadvertent—can hinder the implementation and administration of exchange programs.

At the same time, overly specific provisions can undermine the intent of exchange policies. For example, mandates on program participation—such as requiring a certain number of exchanges per year—may not reflect the needs, goals or capacity of the implementing agency, but could compel it to focus on the quantity instead of the quality of exchanges.

To avoid policy design challenges, agencies seeking a talent exchange authority from Congress should lay the groundwork for the necessary legislation.

Agencies should convene an internal working group when developing the case for an exchange authority. The working group—which should include stakeholders such as the designated agency ethics official and attorneys from the office of general counsel, in addition to subject matter experts, potential supervisors of exchange participants and, when appropriate, senior leaders—should take the time to learn about the potential benefits and challenges of talent exchanges from the managers of existing federal programs. It also should assess agency capacity to administer a program, identify strategies for guarding against conflicts of interest and select the preferred program attributes, such as the direction and duration of exchanges. With such preparation, agencies are in a good position to educate key congressional committees and stakeholders about the value of and their needs for an exchange authority.

Likewise, members of Congress should design exchange policies in collaboration with the implementing agencies when possible so that the authority provides the agencies with the flexibility and guidance necessary to ensure that the program is successful.

If statutory authorities are not conducive to effective exchange programs, agencies can seek policy changes. The Department of Veterans Affairs, for example, is proposing legislative amendments to its Executive Management Fellowship authority to clarify program eligibility and to permit shorter exchanges, among other things, in an effort to make the program more attractive to potential partners and participants.

Program Implementation and Administration

Implementing exchange programs can be complex. Agencies need to figure out how to work productively with entities that operate beyond their control. They also need to be careful that each exchange complies with federal laws and regulations—especially those pertaining to ethics.

Working groups convened by agencies to design talent exchange policies should consult on program implementation efforts as well. Agencies that receive an exchange authority without the support of such a working group should convene internal stakeholders and ethics experts to advise on program implementation.

To implement its Public-Private Talent Exchange Program, ODNI formed a working group consisting of representatives from the 18 intelligence agencies it oversees. The group developed program guidelines and a strategic plan based on ODNI’s exchange authority. It also designed a pilot program and considered how to recruit private-sector exchange partners. Another outcome of the working group is that the agency representatives could become champions of the program and help recruit participants in their respective agencies.

Federal resources outside of an agency also may be of help. Agencies may seek the advice of the Office of Government Ethics when developing program guidelines to identify and avoid conflicts of interest. They also can talk to federal managers of existing public-private talent exchanges to learn from and build on their experiences.

The time and effort of this upfront work—as well as staff dedicated to it—are necessary to ensure that programs not only comply with their policies and federal ethics rules, but also best serve their agency, private-sector partners and individual participants.

Likewise, the challenges of running talent exchanges can be minimized by investing staff time in program administration. The following recurring steps are crucial to effective exchange programs and involve relationship management, which can be time-intensive and difficult to automate.

- Recruiting (new or returning) private-sector partners and individual participants.

- Matching the skills of participants to their hosts and identifying how the exchange can be mutually beneficial for all involved.

- Identifying and preventing conflicts of interest.

- Remaining engaged with participants and private-sector partners throughout the exchange.

- Evaluating the exchange experience and disseminating what is learned.

Relationship management, moreover, isn’t limited to communication between federal program managers and their private-sector counterparts. Program managers also maintain connections to federal and private-sector program participants, their supervisors, relevant subject matter experts and the designated agency ethics official, among other stakeholders.

“Communication is crucial to the success of our Public-Private Talent Exchange, and a priority of the DOD’s Office of Human Capital Initiatives,” said Cathy Dunleavy, a senior human capital manager of that office—which is part of the Office of Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and is responsible for administering and coordinating the exchange program. “Good communication facilitates the best possible exchange matches and ensures a rewarding experience for all participants.”

Given the importance of relationship management and institutional knowledge to cross-sector talent sharing, turnover of exchange program managers can be disruptive to programs. For this reason, civil servants should manage exchange programs instead of political appointees, according to DHS’s Wollenhaupt, because the nature of political appointments “doesn’t provide the continuity and consistency that the business community expects.”

Ethical and Legal Issues

Preventing conflicts of interest and other ethics violations—as well as perceptions of their possibility—is a responsibility that demands close consideration by agencies implementing and managing talent exchanges.

As established in federal regulations, “Public service is a public trust.” Therefore, “Each [federal] employee has a responsibility to the United States Government and its citizens to place loyalty to the Constitution, laws and ethical principles above private gain.” Ensuring the integrity of this commitment requires civil servants to adhere to a set of federal ethics principles that prohibit, among other things, financial conflicts of interest, providing preferential treatment, and seeking or accepting gifts from private-sector partners.

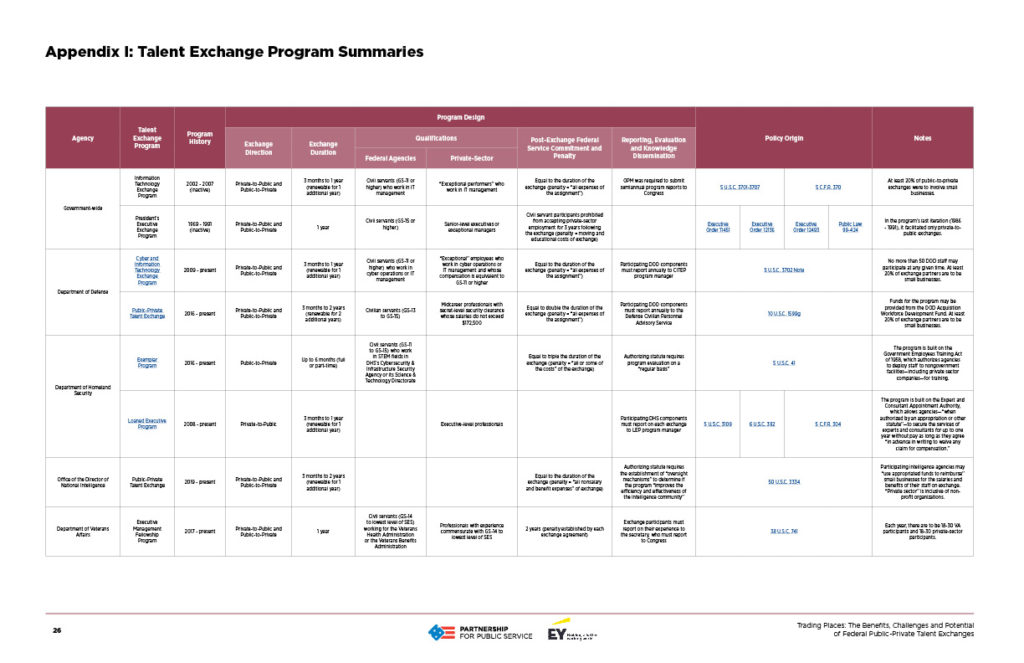

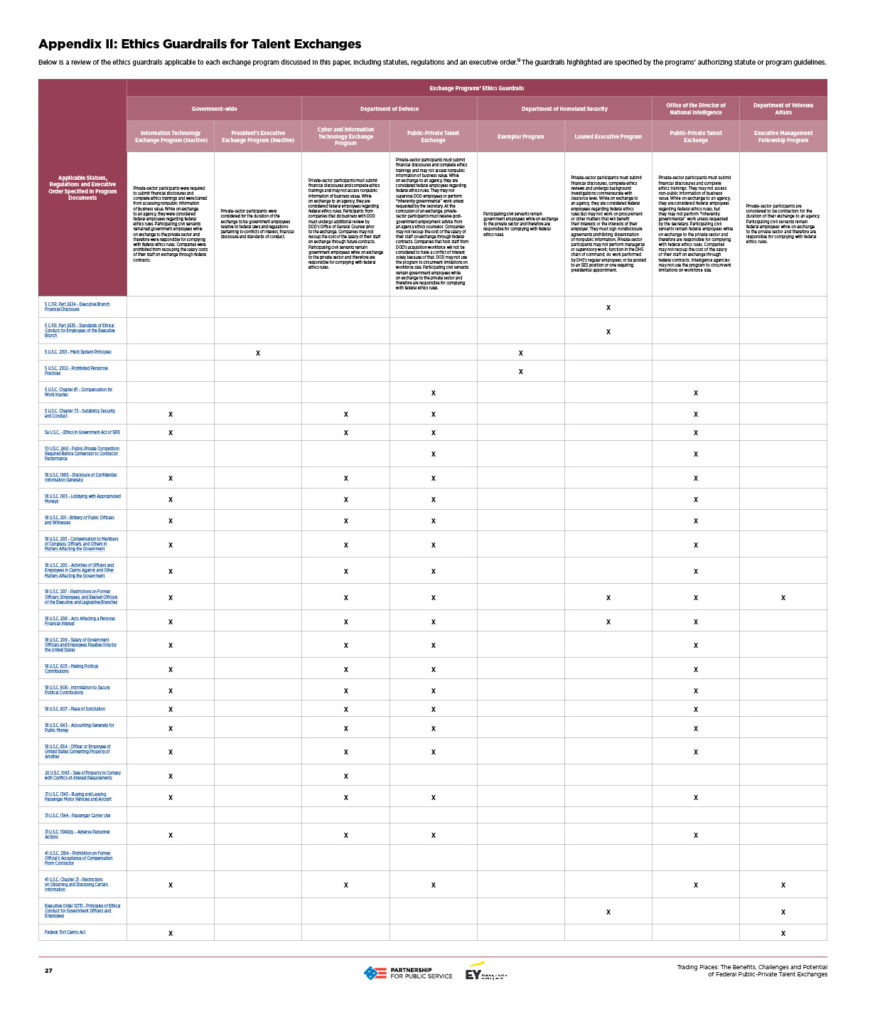

Federal ethics laws—including those in the criminal code—prohibiting financial and other conflicts of interest are important safeguards for talent exchanges, ensuring that participating agencies, private-sector partners and individuals do not intentionally or inadvertently misuse them. To that end, ethics rules apply to federal employees on exchange to the private sector as well as to private-sector professionals exchanging to a federal agency—who are considered to be federal employees relative to the rules for the duration of their detail, according to the Office of Government Ethics. (See Appendix II: Ethics Guardrails for Talent Exchanges to learn more about which ethics rules apply to which exchange programs.)

In assessing the ethics challenges of public-private talent exchanges, OGE has expressed concern about agencies hosting private-sector professionals. OGE warned that private-to-public exchanges may experience “heightened risk of financial conflicts of interest” as well as “divided loyalties” given that professionals hosted by an agency continue to receive their private-sector salary.

Existing talent exchange programs, according to their managers, have been able to avoid conflicts of interest because of good policy design, program implementation and management. Nonetheless, federal leaders and their private-sector counterparts may be hesitant to use exchange mechanisms without further understanding of how agencies can avoid ethics challenges. For example, businesses may be concerned that hosting a civil servant or sending their staff to a federal agency could delay the finalization of or even disqualify them from government service and procurement contracts. Agencies, meanwhile, might want to avoid the potential of improper use of nonpublic or proprietary information.

Such concerns are not insurmountable. With clear guardrails in an exchange program’s statutory authority, due diligence and time may be all agencies need to implement procedures to identify and prevent ethics issues. Thoughtfully designed exchange agreements, for example, can prevent ethics concerns that could scuttle contracts between an agency and its private-sector exchange partner if they create a “firewall” ensuring that exchange assignments do not result in any advantageous business insights for the partner.

Because prevention of conflicts of interest and other ethics violations is a matter of individual and collective vigilance, it is important that all exchange participants understand the application of federal ethics rules and how to watch for, recognize and avoid conflicts of interest. Clear program guidelines can help to this end. Better yet, agencies can provide ethics training to federal and private-sector participants. Agencies can also share their experiences of establishing ethics guardrails to help other agencies implementing an exchange authority.

OGE is available to consult with agencies that are implementing talent exchange policies and programs to provide its expertise as the supervising ethics office.

Agencies can also refer to OGE’s recommendations for designing talent exchange policies and implementing and managing related programs in compliance with federal ethics rules. To learn more, see Appendix III: Office of Government Ethics Recommendations for Public-Private Talent Exchanges.

Finally, agencies may develop additional tools to avoid ethics concerns. ODNI, for example, worked with its general counsel to develop a checklist of potential conflicts of interest—and ways to avoid them—to be distributed to all 18 intelligence agencies.

Exchange Recruitment and Selection

Agencies with talent exchange programs face three challenges related to recruiting and selecting exchange partners and participants.

First, federal supervisors concerned about staff capacity may be reluctant to let a direct report do an exchange—and this reluctance may be greater regarding more senior staff as well as longer-term or full-time exchanges. Talent gaps are disruptive—even when temporary—and not easily filled. Civil servants are not widgets, and their networks, institutional knowledge and working style are not easily transferable.

The second recruitment challenge is finding federal employees for public-to-private exchanges. Civil servants may not understand the exchange program and its potential benefits. As a result, they may perceive time away from their agency to be unrealistic or even detrimental to their career, or they may decide that the effort of the selection process—including the work and exposure of filing a financial disclosure form—is not worth the unknown benefits of exchanges.

Socializing exchange programs with staff and supervisors—through outreach events, engagements with existing communities of practice and other agency cohorts, or even a clear online FAQ page—is a good way to overcome these challenges.

At the same time, targeted recruitment of federal staff based on their career level and skill set is better than indiscriminate recruitment, which could attract people to exchanges for the wrong reasons. Sending an agency-wide email seeking program participants, explained Massey of the Veterans Health Administration, could result in “1,000 people that aren’t really happy in their current work that think, ‘This is going to be great—I get to go away for a year’”—which could complicate and prolong the selection process. All staff recruitment efforts, however, should take active steps to avoid intentional and unintentional bias to ensure exchange programs are inclusive and equitable.

The third recruitment challenge—which some managers of federal exchange programs say is the hardest—is recruiting private-sector partners and selecting private-sector participants.

While many potential partners may have experience working with agencies through federal contracts, most, at this point, do not have experience with federal talent exchanges. The unfamiliarity of exchanges—especially the ethics review, financial disclosure and security clearance processes that precede them—may be a disincentive to companies as well as their employees.

Additionally, perceptions that exchanges could disqualify or otherwise interfere with current and future federal contracts—which can be prevented through well-designed exchange policies and well-managed programs—could dissuade participation.

Finally, because the private sector is generally quicker than the federal government to adopt new technologies and evolve management practices, some companies may not perceive that they will learn much through an exchange with a federal agency. And without this knowledge-sharing benefit, companies may decide the opportunity costs of temporarily deploying staff to an agency are too great. This may be especially true for small companies.

Goals, Roles and Position Alignment

Cross-sector cultural tensions are a normal part of public-private talent exchanges, which include not only the learning curve of onboarding but also the translation of workplace policies, practices and norms.

For civil servants and private-sector professionals, experiencing new procedures and institutional expectations can be both invigorating and daunting. While managers of current federal talent exchange programs do not cite cultural tensions as a big challenge, it should be accounted for when recruiting participants and evaluating individual exchanges.

Private-sector professionals exchanging to an agency, for example, may have little or no previous experience working with the federal government, and as a result they could have trouble adapting to federal processes and workplace culture.

Civil servants on exchange could experience similar difficulties. Furthermore, federal staff may find that public-to-private exchange assignments do not match their experience and career level or that it is difficult to earn the trust of their new private-sector colleagues, especially when exchanging to a company with a strong institutional culture or a lengthy onboarding process.

As Meghan Chu, a civilian employee of the Navy who participated in DOD’s Public-Private Talent Exchange program, said of her host company, “They’re very big on networking, finding your own work—things that you can’t really do in [an exchange that lasts] six months.”

Well-designed onboarding processes—as well as ongoing “over the shoulder” support and facilitated networking with colleagues—can ease exchange-related learning and cultural integration and foster trust, according to William Malyszka, the deputy chief human capital officer and director of the Division of Human Resource Management of the National Science Foundation, which hosts experts and management professionals from academia and industry through its Rotators Program.

In addition, people doing longer or full-time exchanges may experience greater trust with their temporary colleagues than those doing shorter or part-time exchanges.

“It really was valuable to be there full-time because there were occasions when the projects got very intense,” said James McLain of the Veterans Health Administration, who participated in a full-time, yearlong exchange with a healthcare corporation through the Executive Management Fellowship Program. “I think the facility that’s accepting you to be a fellow within their organization may not see the program to be a benefit for them if you just could suddenly disappear…. There’s an expectation that you’re going to be there for them.”

Clear communication between agencies, their private-sector counterparts and individual exchange participants about the scope and responsibilities can also help. Participants with realistic expectations about their goals and assignments are better prepared for an exchange than those without such clarity.

Furthermore, because each experience is different—depending on the exchange host and assignment as well as its length and timing—agencies should encourage civil servants and private-sector professionals to understand their host’s culture and priorities before deploying. Without this preparation, McLain warned, “What you go into may not be why you’re there.”

Post-Exchange

Talent exchange programs typically include a post-exchange service requirement—which is an agreement to continue working in the federal government for a set time, often equal to the duration of the exchange—and a financial penalty for not meeting it, generally the direct cost of the exchange. Such mechanisms are designed to prevent exchanges from being used by private-sector partners as recruitment tools.

While several of the federal managers of exchange programs noted the possibility for exchange-related attrition, none could recall an example of it. Furthermore, several said that commitment to public service counterbalances the attraction of the private sector. As one government employee who exchanged to the private sector put it, “I believe in the mission.”

Civil servants reintegrating into their agencies following an exchange also could experience challenges—such as feeling out of the loop or experiencing eroded relationships with colleagues—though federal exchange program managers and participants interviewed said they have not perceived this problem and that reintegration typically goes well.

Reintegration appears to be easier for staff who do not experience disconnection from their agency while on exchange—including those who remain in routine contact with their supervisor, those who develop a post-exchange plan with their supervisor and those who do shorter or part-time exchanges. As noted by Milo Quiroz of the VA, who did a part-time exchange at a hospital across the street from his medical center, “I didn’t come back to a foreign place.”

Finally, it is important to design and implement evaluations and to develop mechanisms for sharing what has been learned to highlight the benefits of the exchanges. Both efforts require dedicated time from exchange program managers, preferably those with evaluation expertise.